From Perception to Precision: How Farmer’s Insights and Soil Science Can Shape the Future of Regenerative Agriculture.

How do farmers’ perceptions of the health of their soil compare to laboratory results? How can comparing perceptions and laboratory tests influence the use of regenerative agriculture practices by smallholder farmers? These are some of the questions Postdoctoral Associate Jordan Blekking from the Department of Global Development at Cornell University, and, a recent recipient of a Polson Institute for Global Development grant, wanted to study. We were excited to have the opportunity to work and learn alongside Blekking, who selected 175 of Development in Gardening (DIG) trained farmers for his study. By partnering in his research, DIG could learn more about the effectiveness of our program and gain insights for future programming.

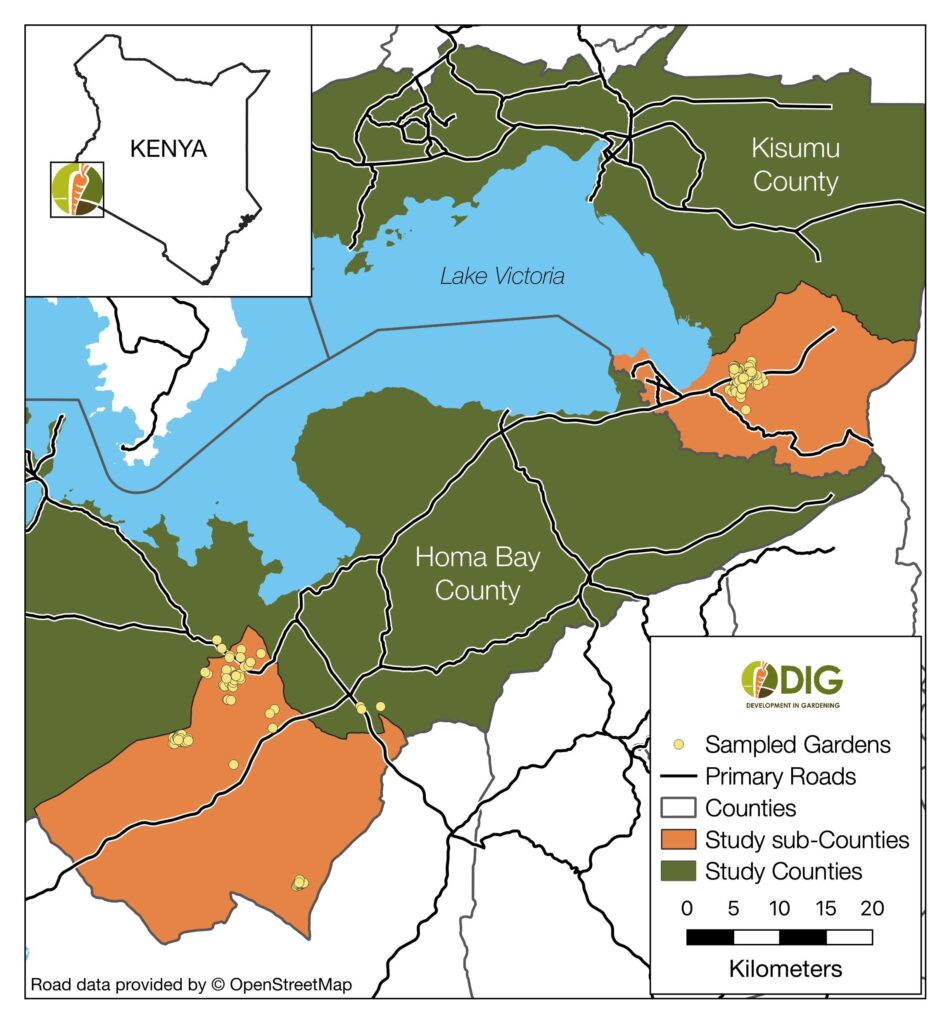

Our mission at DIG is to improve the nutrition and livelihoods of some of the world’s most uniquely marginalized people by teaching them to plant regenerative gardens that grow health, wealth, and a sense of belonging. Blekking’s choice to work with several groups of DIG trained farmers throughout Homa Bay County and Nyakach Sub- County in Kisumu County, Kenya meant that he was studying some of the most marginalized and challenged farmers in the country, assessing their success could influence thousands more in the future.

How do farmers’ perceptions compare to scientific reality?

This partnership with Blekking focused on two key areas: 1) understanding how farmers’ perception of their soil health matched with actual soil quality, and 2) identifying how this knowledge could better farming practices.

The pressing issue is that modern agricultural practices incentivize farmers to use inorganic fertilizers to add nutrients to the soil, but this approach is extremely costly, can increase soil acidity, and reduce soil health overall. Most farmers rely on personal observations to assess their soil health, which can be effective, although not always precise. Scientific soil testing provides concrete data on nutrient levels, pH, and other critical aspects of the soil. This data, when communicated for understanding back to the farmers, further incentivises them to make informed decisions about best soil management plans. For instance, Herina Aoko, a 60-year-old farmer who has been participating in DIG’s Farmer Field School program, shared;

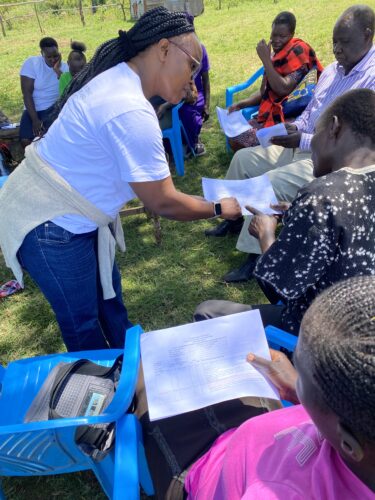

“I didn’t know that soil can be tested and the deficiency of nutrients be determined. During the years I have been farming, the only way I used to determine deficiency of nutrients is by indication of low yields. Thanks to DIG, I now know soil can be tested for specific nutrients and the best recommendations can be made. According to my soil test results, I have realized my soil nutrients are generally very low, and I am going to improve it, just as DIG has advised me, by adding compost to my soil.”

Herina’s experience highlights the gap between traditional methods of assessing soil health and the precise data provided by scientific soil testing. It also illustrates the risk farmers take by waiting to act until harvest season, which is often too late and can result in a significant loss in yield. Scientific soil assessments can empower farmers to make informed decisions that can lead to more productive land over time and gain greater success with regenerative farming practices, like the practices promoted in DIG’s Farmer Field School program.

Rose Oremo, a 47-year-old farmer from DIG’s Jimo Farmer Field School group reflected on her soil test results:

“I have waited for these soil test results, and, thanks to DIG, I finally have them with me. I am not shocked with the results; it was obvious my soil nutrients would be very poor. I have been farming continuously for the last 20 years on the same piece of land where the soil sample was collected without replenishing it. But since DIG trained us on ways of improving soil fertility, I have been making an effort to add compost. I hope in the next year or two I will see improvements.”

Rose’s anticipation, and subsequent validation of her soil’s poor nutrient status, underscores the importance of scientific testing in confirming what farmers have long suspected. This validation not only affirms their experiences; it provides them a clear path forward for soil improvement.

“It doesn’t have to be a mystery,” says Olivia Nyaidho, DIG Kenya’s Executive Director. “We can use the scientific findings to target our response and feed the soil what it needs to better feed us. When we cultivate the earth in regenerative ways, it always gives back.”

How do findings enhance soil health and farmer success?

This full circle approach ensures that farmers, like those trained by DIG, receive accurate soil health information, enabling them to make informed decisions about their land. Through this process, farmers gain a deeper understanding of their soil’s condition, are able to validate their observations and refine their practices. The continuous exchange of information empowers farmers to adopt targeted interventions, leading to healthier soils and improvement in crop yields.

Moreover, the techniques we teach at DIG significantly enhance soil health, forming a crucial component. “It’s an iterative feedback loop that builds trust and resilience for these farmers,” says Nayidho, “and that’s our goal, give farmers the understanding and the tools they need to thrive for generations to come.”

This map highlights the sampled gardens within Homa Bay County and Kisumu County in Kenya. The orange areas represent the study sub-counties, and specific sampled garden locations marked. This research aims to compare farmers’ perceptions of soil health with laboratory results, enhancing sustainable farming practices in these regions.